Tax Law Center Prepared to Hit the Ground Running

“This is an exciting time for the Tax Law Center to launch, as there are so many near-term opportunities to try to contribute to advancing sound tax policy with detailed legal input, in ways that help us build a foundation for doing this work well in the long term” Huang says.

“Our focus now is helping to prepare sound tax provisions that could move in many different legislative packages, supporting their implementation through the regulatory process, identifying and developing other ways to improve tax regulation, and continuing to monitor the courts for decisions that are important to tax law and policy.”

Ultimately, the beneficiaries of this regulation work will be low- and moderate-income households, says Danielle Goonan, The Rockefeller Foundation’s Managing Director, U.S. Equity and Economic Opportunity Initiative. “For those battered by onerous taxes, confusing guidelines and more than their share of audits, the center’s début comes not a moment too soon.”

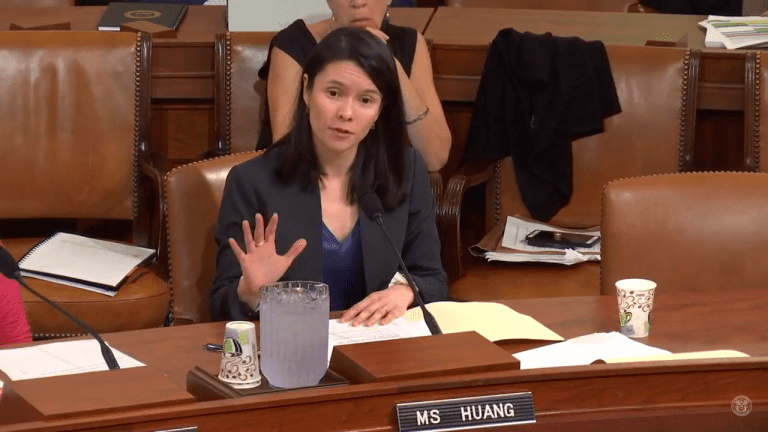

Huang Testifies Before House Ways and Means Committee

Download Huang's Testimony

The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities.

One year ago, in February, which discussions about creating the center were already well underway, Huang testified to the House Ways and Means Committee about inequities in tax enforcement. She mentioned, for example, how underfunding of IRS enforcement “empowers tax avoiders and evaders, including certain large corporations and businesses, while hurting honest tax filers.”

Since 2010, she noted, IRS tax enforcement has been cut by 24 percent in inflation-adjusted terms, even as the number of tax returns has grown by about 9 percent.

“The steep decline in audits for high-income individuals stemming from IRS underfunding means that low- and moderate-income households claiming the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) are now audited at roughly the same rate as the top 1 percent of filers, even though the former are responsible for less than 10 percent of the tax gap due to underreporting, while the latter may account for as much as 70 percent,” she told the committee.

Both horizontal and vertical equity are needed for a tax system to be fair—in other words, taxpayers similarly situated pay the same amount of taxes, and those with more income or property pay more than those with less. But the many individual tax law and policy decisions that together determine whether or not the tax system is in fact equitable can themselves be very complex and opaque.

In-The-Weeds Work with Major Consequences

Income tax returns are the most imaginative fiction being written today.

“Technical decisions on tax regulation can seem opaque even to policymakers themselves,” says Huang. “This is in-the-weeds work. The complexity can obscure how consequential these decisions are. But there are public-minded tax practitioners out there who realize that.”

Lily Batchelder, the Tax Law Center’s founding Faculty Director, agrees. “Tax is one of the most heavily lobbied areas of the law, and overwhelmingly by private interests, which often employ technically complex legal arguments in litigation, and in lobbying on regulations and legislation,” she says. “The Tax Law Center will aim to provide a partial counterweight to this tilt toward private interests through a rigorous, technically-grounded public interest voice.”

The financial requirements of the Civil War prompted the first American income tax in 1861. At first, Congress placed a flat 3 percent tax on all incomes over $800 and later modified this principle to include a graduated tax. The 16th Amendment, ratified in 1913, enshrined the income tax in the Constitution.

As years passed, the tax code became more complex, and often reinforced income inequality.

For example, during her congressional testimony, Huang also briefly focused in on pass-through taxation, which she called “the largest source of the tax gap.”

“Instead of addressing pass-through tax non-compliance,” she noted, “the 2017 tax law created a costly, complex new deduction for pass-throughs. The top 1 percent of households will get 61 percent of the benefit from the new deduction… while the bottom two-thirds will get just 4 percent.”

As one tax advisor, Jeffrey Levine of BluePrint Wealth Alliance and Fully Vested Advice, told a conference for personal financial advisers:

“This is, without a doubt, one of the biggest areas of planning that we can have under the new law. This is why, in large part, they should have just renamed the [2017 tax law] the tax professional, lawyer and financial advisor job security act of 2017.

The [pass-through] deduction leaves a gaping hole in the tax code, and the goal by the end of the presentation today is to make you guys the bus drivers, or the truck drivers, to drive right through that hole with your clients.”

This complex new provision is one of the reasons why the 2017 tax law increases income inequality, especially racial inequities. While the highest-income white households make up just 0.8 percent of all households, they receive 23.7 percent of the total tax cuts from the 2017 tax law, far more than the 13.8 percent that the bottom 60 percent of households of all races receives, the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy estimates.

Huang called on legislators to instead “directly boost the incomes of low- and moderate-income workers and families who were largely left behind by the 2017 tax law by enacting proposals to strengthen the EITC and Child Tax Credit.”

Huang: The Time is Ripe for Change

Tax complexity itself is a kind of tax.

Huang, who received her initial economic and legal training in New Zealand, was drawn to tax law the way some people are drawn to crossword puzzles—except that tax regulations, she says, impact the very fabric of society.

“With a law and economics background, I didn’t know tax was the area I wanted to go into. But I was drawn to it because it spoke to my interest in detailed, intellectually satisfying work, but at the same time, it touches every individual and every business and offers the opportunity to achieve better outcomes for families and businesses and cities, states and nations.”

The Tax Law Center intends to bring aboard subject matter experts in a number of areas of tax law, and these staff will collaborate with tax lawyers in academia and practice. The end of Year One will look like a success, Huang says, if “we have put in place some of the foundational infrastructure needed to do this work well, including systems for monitoring and prioritizing among the flood of tax regulations, cases, and bills to be most impactful, and we have engaged a team of public-interest-minded allies.”

“The time is ripe,” she says with conviction. “We are building off the work other organizations have done, and taking it one step further. And this is really important for groups interested in achieving greater opportunity and more equitable economic future.”

Related Updates

A Look at EITC: Don’t Leave Your Money on the Table

An exploration of what the Earned Income Tax is, and what it isn’t.

More This is the underpinning of the Tax Law Center, and The Rockefeller Foundation jumped in to help support it out of a conviction that its work is ever more important as the Covid-19 pandemic and resulting economic crisis have highlighted the U.S. economy’s deep inequities and fragilities. The Tax Law Center will promote economic justice by helping promote the public interest in tax policies and litigation.

This is the underpinning of the Tax Law Center, and The Rockefeller Foundation jumped in to help support it out of a conviction that its work is ever more important as the Covid-19 pandemic and resulting economic crisis have highlighted the U.S. economy’s deep inequities and fragilities. The Tax Law Center will promote economic justice by helping promote the public interest in tax policies and litigation.