Some 80,000 people live there in floating houses that rise and fall with the ebb of flood waters, surrounded by flooded forests and floodplains. Most depend on fish for their livelihoods. This required another adjustment, Sochet noted. “I didn’t have the traditional skills of a fisherman. My wife had to teach me a lot.”

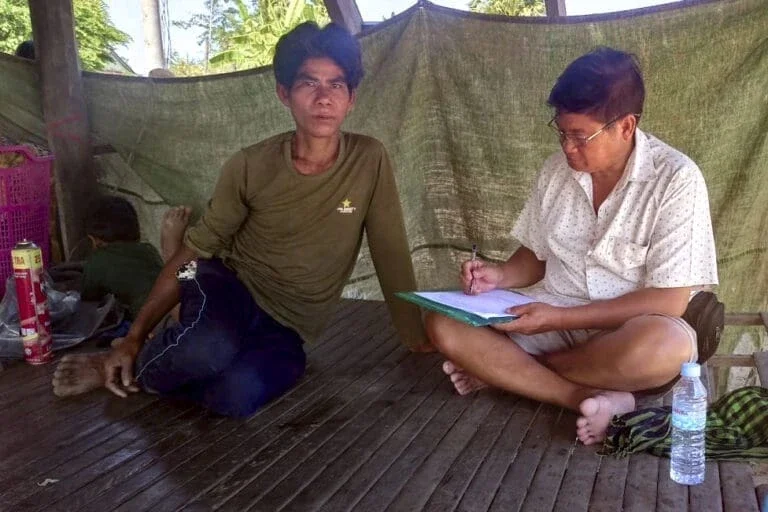

In time, he mastered those skills, eventually opened a floating shop, and then became Chief of the Coalitions of Cambodian Fishers (CCF).

From this position, Sochet, now 65, is focused on helping his adopted community survive the challenges of climate change that threaten their way of life.

Lower Water Levels, Fewer Fish

From November to May, Cambodia’s historic dry season, the Tonle Sap drains into the Mekong River at Phnom Penh. When the year’s heavy rains begin in June, the Tonle Sap changes direction and backs, making the lake as much as five times larger while flooding nearby fields and forests and providing a breeding ground for local fish species.

More than 500,000 tons of fish come out of the Tonle Sap each year. To put this in perspective, all of North America’s freshwater lakes and rivers combined produce about 450,000 tons of fish annually, Brian Eyler writes in his 2019 book Last Days of the Might Mekong.

In addition to selling fresh fish, the community dries fish and makes prahok, a fermented fish paste storable for many months after the fish harvest. Fish exports account for about 10 percent of the country’s gross national product.

But there are some troubling signs.

Once plentiful fish populations declined by more than 87 percent between 2003 and 2019, hit by the combination of drought, rising temperatures, delayed rainfall, overfishing, and the impact of dams upstream on the Mekong River.

“Certain fish species have already disappeared, and others are endangered,” Sochet said. “Now fisherfolk rely on catching small fish that we wouldn’t have bothered with before.”

This could impact Cambodia as a whole. Fish is the single largest source of protein for some 60 percent of the population of nearly 17 million.

The lake’s water level is also falling. In 2019, it reached a record low. Fisherfolk described the water as shallow, warm, and oxygen-starved.

Sochet repeated the Cambodian proverb “mean tuek, mean trey,” which means “where there is water, there are fish.” The opposite is also true, he said; in shoals, there are fewer fish.

Working To Preserve a Way of Life

Within the floating communities, the ripple effects are enormous.

Because fishing can no longer support families, some send their children to the mainland to work as young as age 15. Many are leaving the lake altogether, moving to urban areas.

Sochet and his wife are among them. His six children and 12 grandchildren also all live on the mainland now.

But he takes his grandchildren back to his floating community for ceremonies and holidays because he wants them to experience it. He would be sad to see that way of life vanish.

“There is a sense of solidarity in the floating communities, more than on land, and a habit of sharing,” he said. “Families are close-knit and spiritual practices are linked to the water and the forest. All that is lost if the communities vanish.”

CCF is part of a coalition of organizations acting to elevate the voices of fisherfolk, and protect local fishing communities and water resources. Sochet also helps his community devise practical ways to diversify their livelihoods while working to strengthen their capacity to manage Tonle Sap, including developing fish conservation pools.

“We have to do something,” he said. “We can’t let climate change wipe out our natural resources.”

More from this series

Building Bridges for Collective Climate Resilience

A six-part series that highlights frontline community voices from those whose lives are being transformed by a changing climate.

READ MOREBangladesh: The “Green Monk” Champions Recycling

The “Green Monk” Champions Recycling: “Buddha told us to live in harmony and balance with our environment.”

READ MORE