Born the eighth of 13 children to an Ethiopian farming family, Zemede Asfaw’s earliest memories are rooted in the land.

He was a sheepherder before he could count his years in double digits, his small hands tangled in warm wool. Soon, those same youthful hands were sinking into the earth, tending crops and absorbing the lessons that would shape his life’s work.

His father, Mr. Asfaw Woldemariam, was a tenant farmer, required to give a quarter of his harvest to the landowner. With a large family to support, efficiency wasn’t a choice — it was a matter of survival. And survival depended on biodiversity.

Zemede, who goes by his given name, watched as his father planted a rich mix of sorghum, maize, beans, and other diverse crops alongside herds of cattle, goats, sheep, mules, donkeys, chicken, and honeybee colonies. Zemede’s family didn’t rely solely on the land they cultivated. They foraged in the surrounding forests, gathering edible wild fruits to add variety and resilience to their diet and fulfill other household needs.

Mr. Asfaw Woldemariam was endlessly hardworking and curious, always returning from travels through three of Ethiopia’s agroecological zones with new plants to try, adding diversity to the food and the plate. Some flourished, others failed — like the cassava shrub he planted, only for a porcupine to burrow under a fence and devour the tubers before the family got a taste.

But every trial, whether a success or a failure, reinforced the same lesson: variety was key.

Zemede (far right in green cap) is joined by a professor, a farmer, and a student as he examines crops grown as part of diversity research. (Photo Courtesy of Zemede)

“I grew up amidst diversity,” said Zemede, now 77. “I observed farmers taking care of their fields in a way that mimicked nature. Farming success meant both food and nutritional security as an inseparable package.”

Decades later, Zemede remains dedicated to that principle. As an ethnobiologist with the Department of Plant Biology and Biodiversity Management at Addis Ababa University, he is a key member of the Traditional Grains Mixture Project, an international study funded in part by The Rockefeller Foundation.

The goal? To see if innovations around an ancient practice — growing mixed grains in a single field — can help feed the world. And the need has never been more urgent.

Dr. Alex McAlvay walking with translator Zeray Romha Sebhatleab to farmers' fields in Northern Ethiopia while carrying out interviews about traditional grain mixtures. (Photo Courtesy Dr. Alex McAlvay)

Dr. Alex McAlvay walking with translator Zeray Romha Sebhatleab to farmers' fields in Northern Ethiopia while carrying out interviews about traditional grain mixtures. (Photo Courtesy Dr. Alex McAlvay)

A Growing Crisis, and the Role of Biodiversity

Globally, crop yields are decreasing due to more irregular and extreme weather, researchers note. Croplands comprise about 12 percent of the world’s total land area.

An anticipated 5-10 percent decline in crop yields is likely in the U.S. Midwest by 2030, according to a recent study using 20 computer models. Nearly 40 percent of all plants face extinction due to factors such as land clearing, over-harvesting of wild species, and changing weather patterns, another study showed.

A farmer holds up a stalk of megamegu, a mixture of multiple varieties of wheat and barley grown in farmers fields in South Wollo Zone, Ethiopia. (Photo Courtesy of Dr. Alex McAlvay)

At the same time, some 733 million people globally suffer from malnutrition or hunger, an increase of 152 million since 2019.

And over 2 billion are affected by “hidden hunger” — micronutrient deficiencies caused by insufficient intake of essential vitamins and minerals, even when caloric intake may be adequate. Hidden hunger occurs across socioeconomic levels and has significant impacts on health, development, and overall well-being.

Biodiversity directly fights both conditions by ensuring stable food production and improving nutrient availability.

Protecting ecosystems, diversifying crops, and integrating traditional food systems into modern agriculture are essential for global food security.

The Necessity of Investing in Biodiversity

“Nutrition security isn’t just about producing more — it’s about cultivating diversity, resilience, and sovereignty,” said John de la Parra, Director, Food Initiative, The Rockefeller Foundation. “As we face escalating climate threats and rising malnutrition, we must look to the knowledge embedded in traditional agricultural systems. These practices, refined over generations, offer solutions that not only sustain yields but also nourish communities and restore ecosystems. Investing in biodiversity is not just a strategy — it’s a necessity for a just and regenerative food future.”

Early results from the Traditional Grains Mixture Project hold promise for greater yields, improved nutrition density, and higher farmer incomes, said Dr. Alex C. McAlvay, a research scientist in the Center for Plants, People, and Culture at the New York Botanical Garden who is helping oversee the research.

The study involves planting a mixture of varieties or crop species in the same field, as opposed to either monocropping where one field is one crop, or intercropping, with different crops in separate rows side by side. Research participants include the Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Wollo University, the New York Botanical Garden, Cornell University, Clark University, and City University of New York. Data is also being gathered from the countries of Lebanon and Georgia.

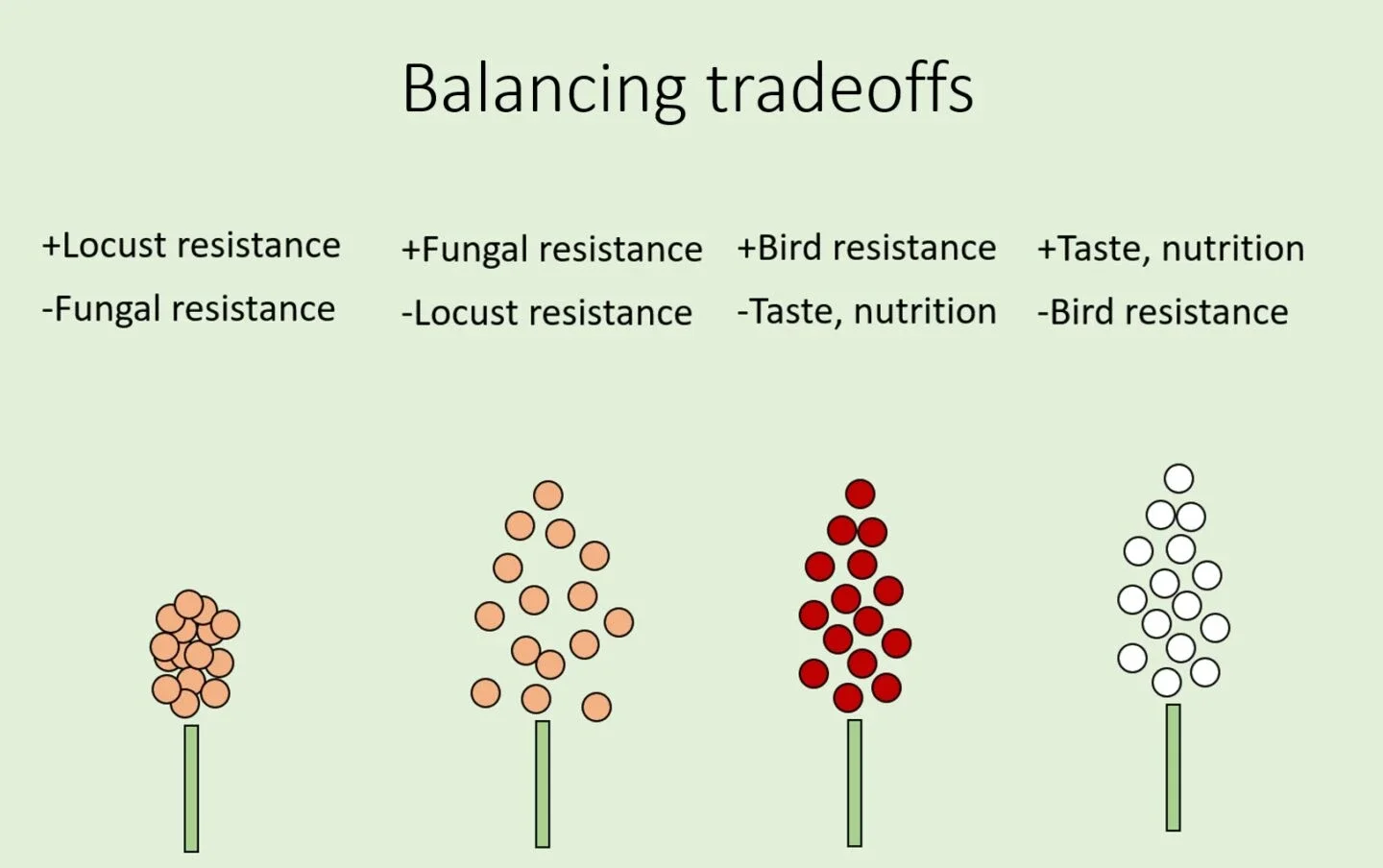

How diverse varieties and species grown in the same field deliver greater resilience. (Photo Credit Dr. Alex McAlvay)

How diverse varieties and species grown in the same field deliver greater resilience. (Photo Credit Dr. Alex McAlvay)

Unlocking the Power of Traditional Mixtures

The ancient method of intermingling small cereal crops is known as maslin. The word refers both to the planting method and a cereals species mixture that can include wheat, barley, rye, and other grains distributed by hand randomly through a field.

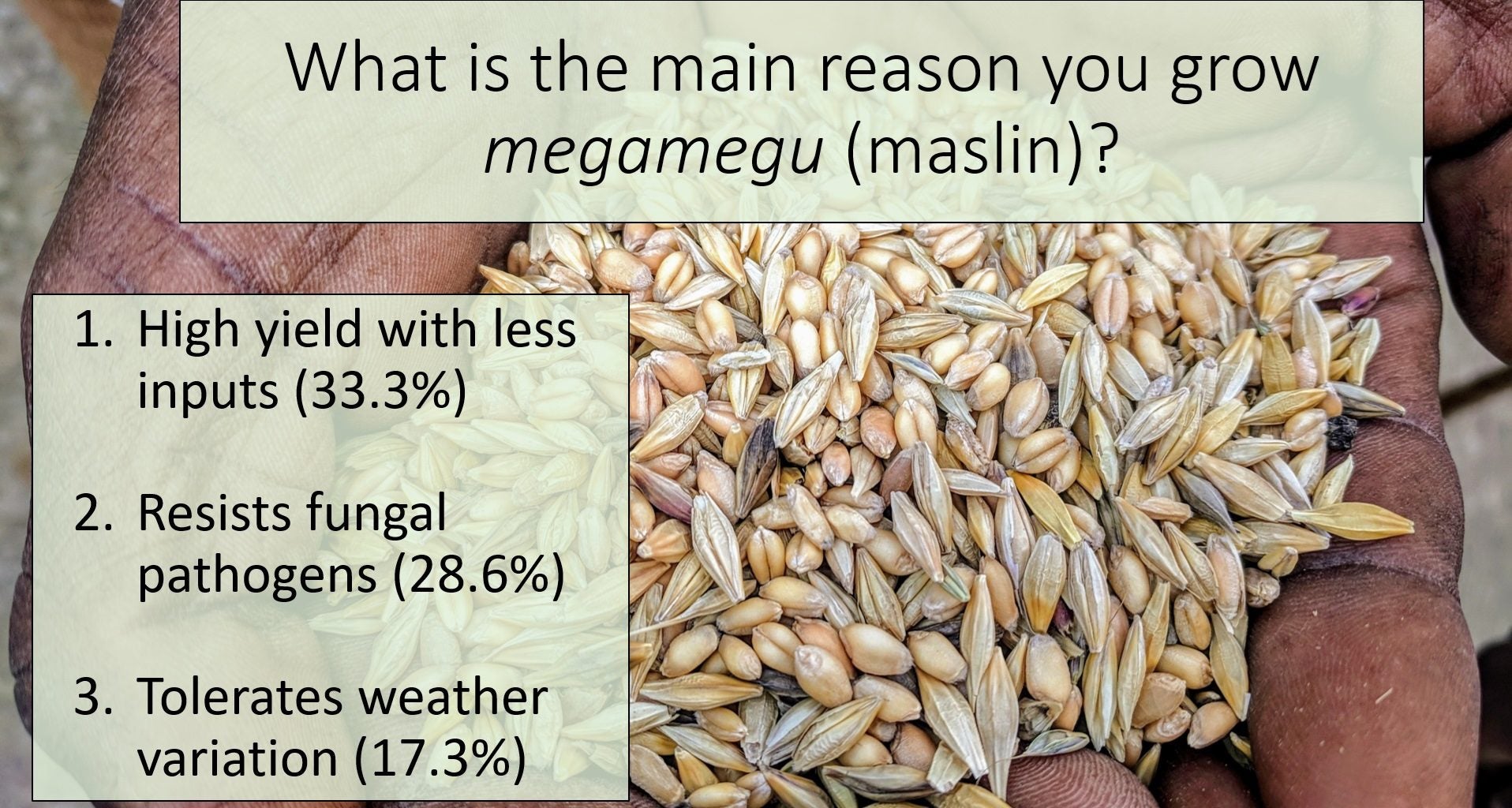

The main reason farmers cite for growing maslin. (Photo Courtesy of Dr. Alex McAlvay)

It’s a method that has been used for over 3,000 years and is still practiced by traditional farmers in Ethiopia and a handful of other countries. The aim is to always produce some grain, even in shifting or extreme weather conditions.

“This work is not just urgent; it’s long overdue,” McAlvay said. “If you look at the grand sweep of history, you see most plants have been grown in diverse mixtures of varieties and species. And it worked. It sustained communities through centuries.”

The Traditional Grain Mixtures Project, which included 1,300 farmer interviews and nutritional analyses, centered on mixtures of wheat and barley, fava bean and field pea, sorghum varietals, and tef varietals grown at three research stations each in the Amhara region, plus 30 farmers per mixture cultivating crops on their land in different proportions and providing data.

The early findings released in January 2025 show that some traditional grain mixtures offer significant yield advantages compared with monocultures, and help farmers manage environmental variations, pests, and pathogens. They also suggest the mixtures could produce more stable yields under varying climatic conditions.

The wheat-barley mixture planted in a 1:2 ratio of barley:wheat, for instance, produced 1.50 times the yield of monocropped barley and 1.20 times the yield of monocropped wheat. For the farmers, this combination produced a 197.8 percent of the net benefit in revenue over monocropped barley, and a 115.4 percent of the benefit over monocropped wheat.

Researchers often work for years to achieve a 10 or 15 percent increase in yields, while this traditional method of regenerative agriculture achieves much more than this without any additional inputs.

Roy SteinerSenior Vice President, FoodThe Rockefeller Foundation

“It is an Indigenous innovation that many look past, but we took the risk in supporting and advancing this research because it supports a vulnerable population and can stand to benefit many others,” Steiner said.

The study also found that farmers who mixed mokake, a sorghum variety that produces well with abundant water, with esmael sorghum, which is more drought-tolerant, were creating more consistent harvests in varied weather conditions.

Mixing crops also seemed to sometimes improve nutritional value; for instance, in the barley and wheat mixture, the barley had higher dietary fiber and the wheat had high calcium, selenium, and beta-carotene.

Farmer Hasan Abagaz and Wollo University Assistant Professor Seid Hassen in Hasan’s mixed barley and wheat field in Kutabir, Ethiopia. (Photo Courtesy of Dr. Alex McAlvay)

“For thousands of years, farmers have adapted to changing conditions by experimenting and learning from the land — but too often, their wisdom is overlooked,” said McAlvay. “These early results show mixed crops can boost yields, improve livelihoods, strengthen climate resilience, and enhance nutrition. Investing in this research is essential if we want agriculture to meet the needs of a growing world.”

Zemede is thrilled to part of the team gathering data to fully understand how biodiversity impacts the nutritional value of crops — “trying to understand in a scientific context the impact of what our traditional farmers have been doing all along — mixing crops on the field to increase resilience and fight food scarcity.”

“The modern world is starting to realize these traditional practices are sustainable, environmentally friendly, and also nutritionally rich,” Zemede said. “Now we’ve gathered clear data to show that. I feel happy to be on the land amid biodiversity. It’s my comfort zone.”