In the past five months, we have witnessed an abrupt, and unprecedented disruption to the institutions, agreements, and norms that have supported global public health for decades. The United States has withdrawn from the World Health Organization, effectively dismantled USAID, and cut 83% of its humanitarian programs. The U.S. is not alone, other nations are scaling back critical development and assistance funding.

At the same time, we face mounting and increasingly complex threats to global health. Historic rainfall is driving outbreaks of infectious disease; extreme heat now claims nearly half a million lives each year and pushes the limits of human survivability; and more frequent, extreme weather is destroying infrastructure and disrupting supply chains, leaving communities without access to essential care.

This disruption at a moment of real peril will put lives at risk in the short and long term.

To meet the mission of public health at this moment, those of us in public health need to admit that the system needs more than a bandage or crutch. As traditional funding sources recede, institutional power shifts, and long-standing systems falter, we have to admit the prevailing system is no longer fit for purpose in today’s world and accelerate the thinking of a global health architecture fit for tomorrow. The top-down, donor-driven models of the past have proven insufficient. We need a system that moves from aid to investment, shifts power and autonomy to the countries most affected, and embraces a system-wide approach to today’s interconnected threats.

From Aid to Investment

In 2024, over half of African countries spent more on debt repayment than on health care. The current global aid system fosters dependency and stifles the development of sustainable systems. By rethinking financing models — so that capital strengthens local economies rather than extracts from them — we can replace vicious cycles with virtuous ones.

This requires a transition from fragmented donor aid to true economic partnerships. Mechanisms such as debt-for-health swaps, catalytic financing, credit rating reforms, and country-specific financing compacts can not only mobilize domestic resources aligned with national priorities but can also open the door to catalytic partnerships with the private sector.

From Donor-Driven to Locally Led

Transforming global health demands investment in local capacity for research, innovation, manufacturing, and health service delivery. That means strengthening universities, research institutions, and local leadership across Africa, Asia, and Latin America — leaders who will shape the future of global health.

For too long, expertise has flowed in one direction — from North to South — with priorities set in Geneva, Washington, and London rather than Nairobi, Chennai, or Lima. This approach has squandered human potential and produced systems ill-equipped to meet local needs. The Covid-19 pandemic revealed the consequences of such imbalance: countries that had invested in local manufacturing capacity fared significantly better than those dependent on foreign supply chains.

Genuine progress requires shifting resources and decision-making power to those closest to the challenges. This will involve difficult adjustments for traditional centers of influence — but the innovations that result will benefit us all.

From Siloed Programs to Systems Transformation

We must break free from the narrow, siloed approaches that have come to define global health. Climate change’s impacts, which will prove the public health threat of our time, demand a holistic transformation across systems of health, energy, education, and food.

We can no longer afford the artificial separations between health and climate finance, between pandemic preparedness and food security, or between city planning and non-communicable disease prevention. Malaria programs must now account for the expansion of mosquito habitats due to rising temperatures. City planners must design urban environments that can withstand extreme heat to protect half of humanity living in urban areas. This integration isn’t theoretical, it is urgent, pragmatic, and essential.

The Path Forward

The seismic disruptions in global health, compounded by economic instability and escalating climate risks, have put decades of development progress at risk. These crises have exposed the fragility of status quo institutions and systems. They also must force a long-overdue reckoning. Too often, the prevailing public health system has reinforced inequity and dependency.

But within this disruption lies a chance to do something different. There is no one individual or institution that can replace the support in the near term. This realization must force all of us in public health not to simply decry what should be but develop what must be: a global health ecosystem that is inclusive, resilient, and truly fit for the future. For too long, well-meaning patches and salves have done nothing but cement dependence rather than enable autonomy.

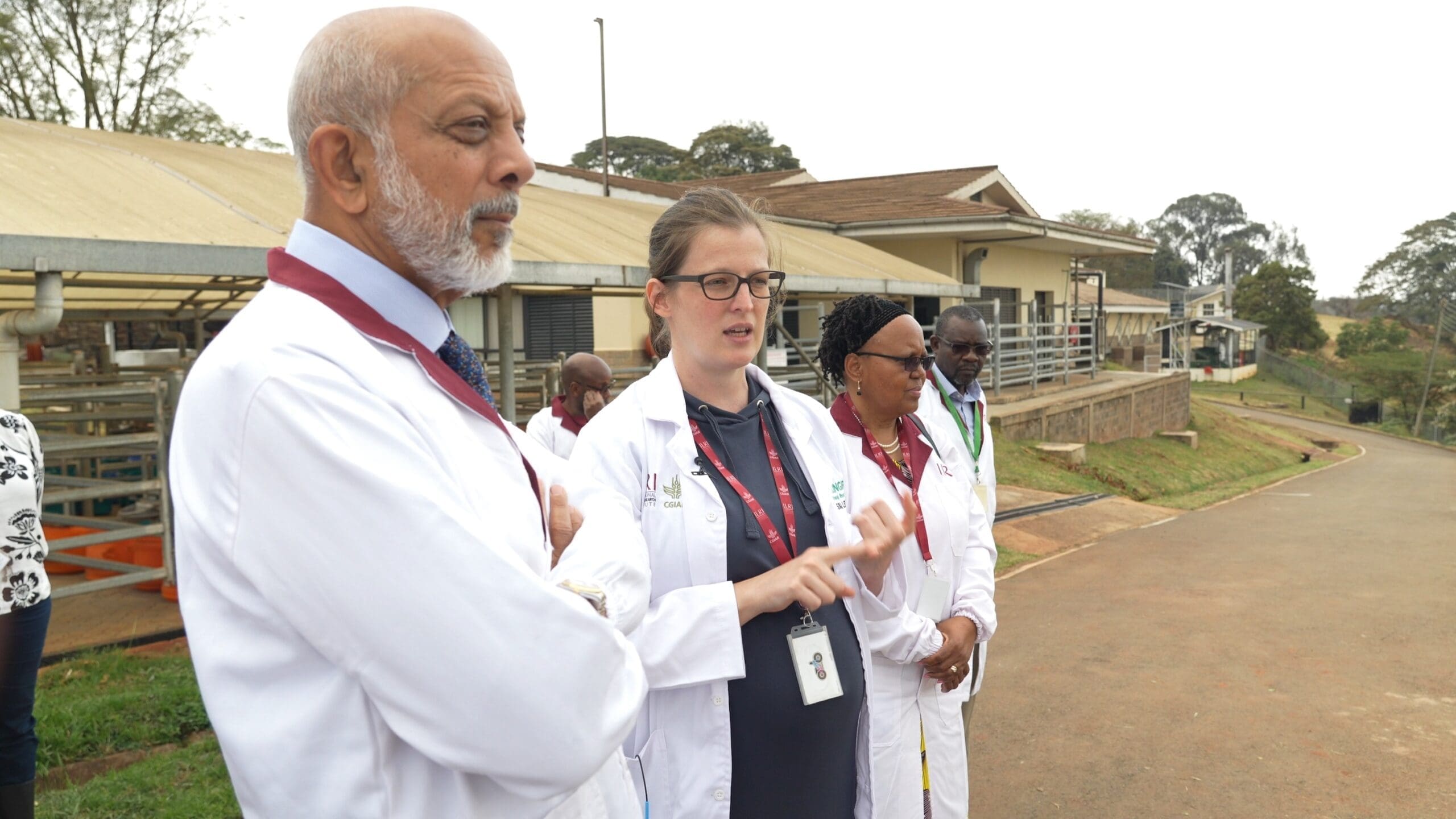

Dr. Naveen Rao, Senior Vice President, Health Initiative, during a visit to discuss pandemic preparedness efforts at the International Livestock Research Institute in Kenya. (Photo Credit Evan Stulberger)

Starting at this week’s World Health Assembly, we can begin the work of trying to make an opportunity of this devastating crisis. The path forward will be complex, but our guiding principle must remain clear: every person, regardless of where they are born, deserves the chance to live a healthy life.

Dr. Naveen Rao is the Senior Vice President of the Health Initiative at The Rockefeller Foundation. He is board certified in internal medicine and is a fellow of the American College of Physicians.