She was not the only victim. Researchers estimate the heatwave claimed nearly 1,400 lives in that single month.

And this is just the beginning. Each new record-breaking heatwave, driven higher and faster by climate change, will push health systems further past their limits.

Rio already had protocols for floods and heavy rains. But not for heat. It took the devastation of November for officials to face what had long been clear: heat is no longer just a feature of the city. It is a lethal threat.

“Recognizing this new reality, we brought the issue to the mayor, who promptly created a working group,” recalled Marcus Belchior, then CEO of the Rio Operations and Resilience Center (COR).

Officially launched in June 2024, Here’s how the Extreme Heat Response Protocol works: Meteorological stations and sensors across Rio track weather conditions, while the CIE integrates this with health metrics like hospital admissions and clinic or emergency visits. The result is an early warning system that can model risk up to three days ahead and trigger alerts when danger looms.

Alert systems are only possible through data — data that give cities the opportunity and time to act and prepare. Being able to predict heat indices, forecast health impacts, and trigger responses in advance was a key part of the process.

Gislani MateusRio de Janeiro Municipal Health Secretary

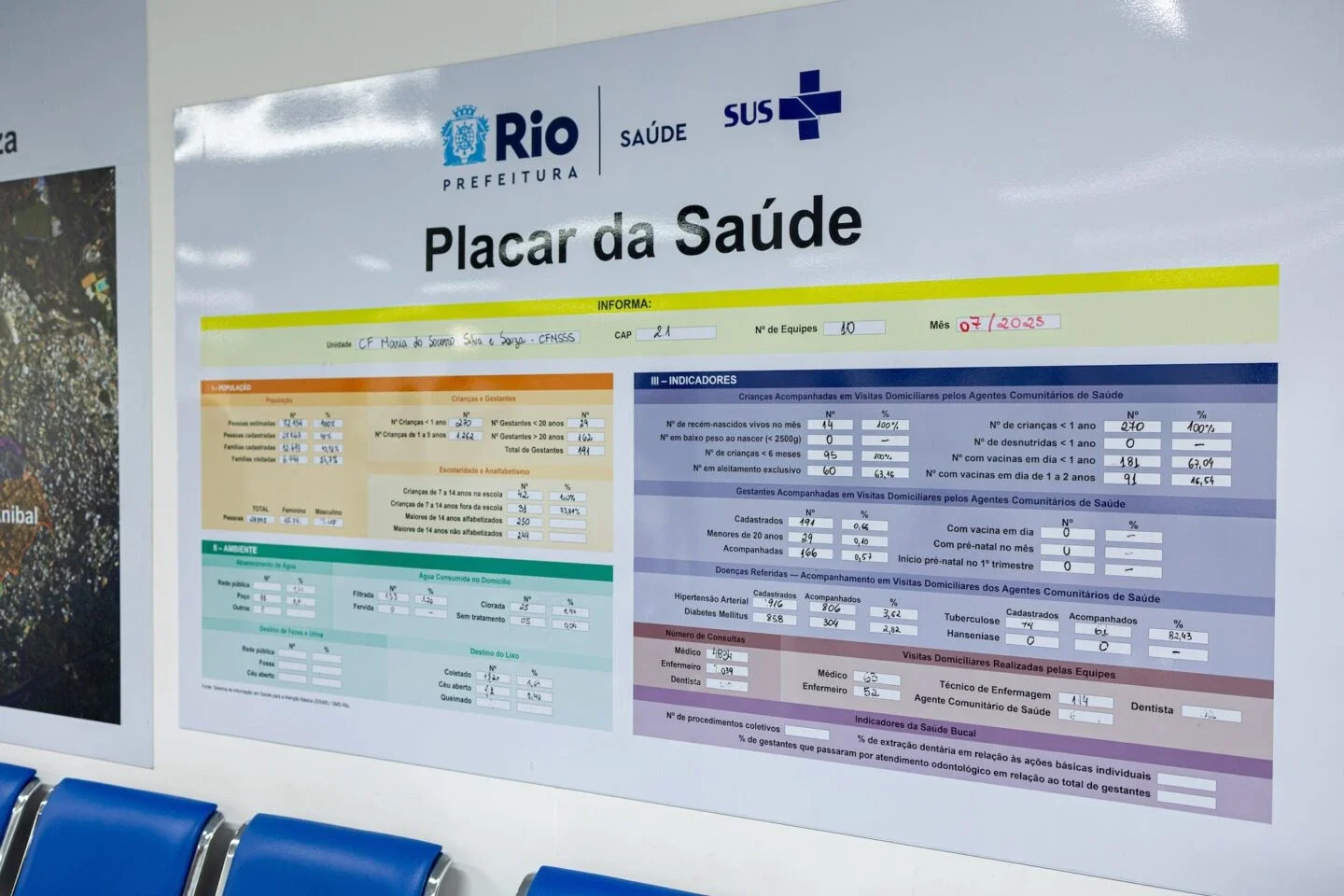

“Since the protocol was implemented, we’ve been able to be ready in advance,” Adams said. The clinic doesn’t simply wait for people to come. “We also have a team that goes out on the streets, looking for people who are most vulnerable during heatwaves — the elderly, bedridden, and small children.”