For many years, British politician Boris Johnson decried the “nanny state”. In a 2004 article titled Face it: it’s all your own fat fault, he argued that obesity was a choice and state intervention would worsen things.[i] Fast forward to July 2020: now-Prime Minister Johnson launches a wide-ranging anti-obesity program in the UK.[ii]

What changed his mind? Covid-19. In April, he was rushed to ICU treatment. About two-thirds of British adults are overweight or obese; this demographic is drastically overrepresented among Covid-19 patients, and Johnson was one of them. He’s since started to exercise and has lost 14 pounds – and realized that obesity is a major public health threat.

Policy, as Johnson himself acknowledged,[iii] should be based on evidence. And there are, actually, many encouraging examples of countries that have used policy to shift dietary patterns for entire populations and thus improve health outcomes.

From North to South: Five policy changes that moved the needle

Excessive salt intake is a major cause of hypertension and heart disease. Finland began promoting salt reduction with public awareness campaigns in the 1970s and introduced mandatory salt labelling in the 1990s. From the late 1970s to 2002, daily salt consumption halved among women, from 12 g per day to 6.5 g per day. Since the start of Finland’s salt reduction effort, sodium excretion levels have decreased 25-30 percent, and along with that blood pressure levels.[iv] Today, at least 20 EU countries have salt reduction initiatives, comprising product reformulation, consumer campaigns, taxation, front-of-pack labelling, and interventions in public institutions.

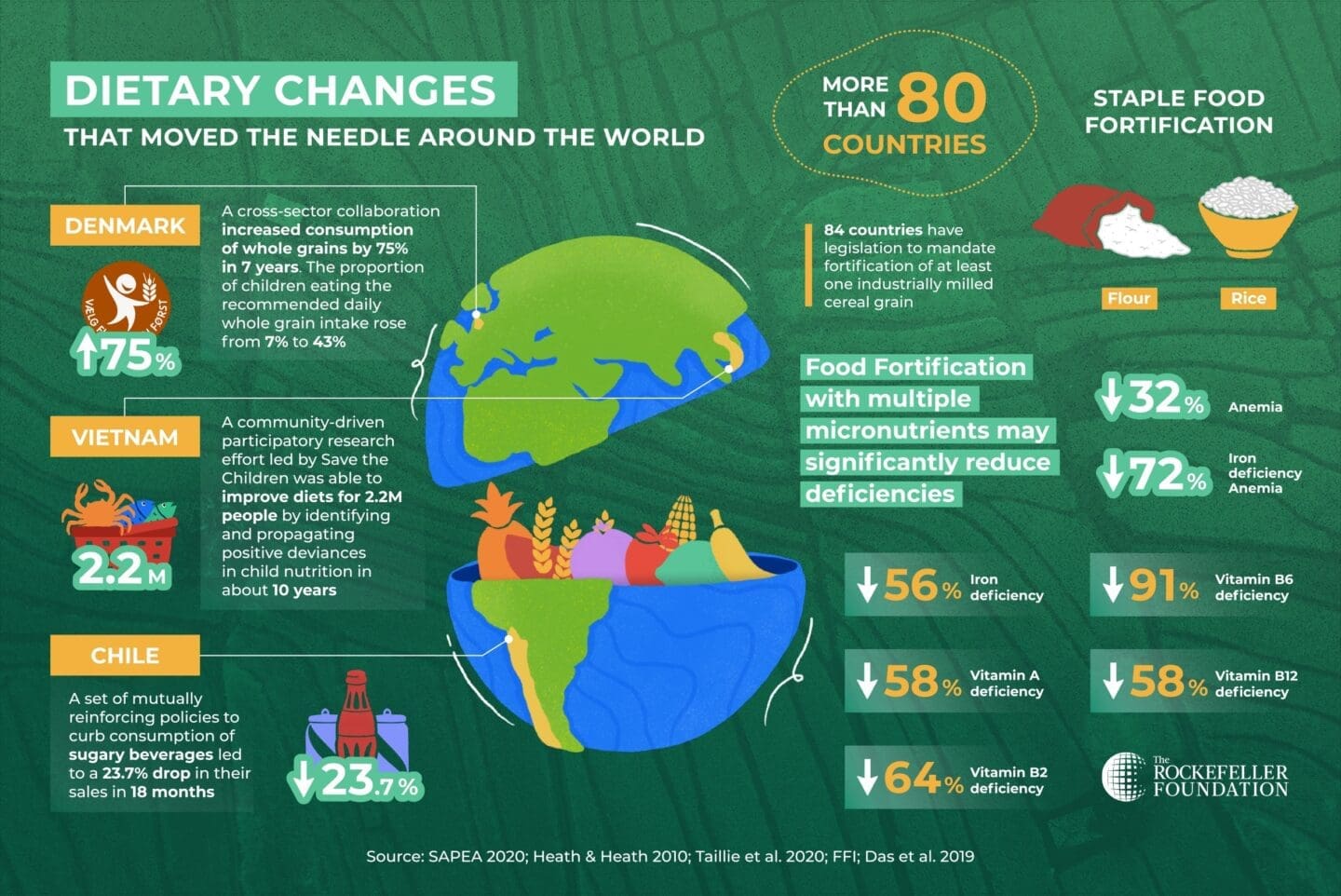

Denmark’s whole grain partnership is another example of large-scale dietary improvement.[v] Whole grain consumption had dropped in the country in the 1990s and 2000s. A cross-sectoral alliance bringing together the government, the food industry, retail, and health NGOs developed an integrated approach to turn the tide and increase whole grain intake across the entire population. This alliance compiled health benefit evidence, gained consumer insights, set targets, issued dietary guidelines, developed a whole grain logo, conducted communication and educational activities, and drove product reformulation.

Between 2007 and 2014, the population’s intake of whole grains increased by 75 percent and more than doubled among children. The proportion of the population eating the recommended intake of whole grains rose from 6 to 30 percent (43 percent for children). The number of whole grain logo-labeled products grew five times.

Denmark also took strong action against trans-fats; consumption of just 5 g of trans-fats per day is associated with a 23 percent increase in the risk of heart disease.[vi] In 2003, Denmark was the world’s first country to ban trans-fats. Within a year, most products on the market were complying with the new limit (2 g trans-fat per 100 g fat). Trans-fat intake among all age groups now stands at about one-tenth of previous levels, and there’s been a significant decrease in cardiovascular-related deaths partly attributable to the drastic drop in trans-fat intake.[vii] Several countries in Europe, the US, and Canada have since instituted similar trans-fat bans.

In 2016, Chile launched a new policy to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages through a combination of measures – taxation, front-of-pack labeling, marketing restrictions, and school sales bans. In 18 months, purchases of sodas dropped by almost 24 percent, a higher decrease than previously observed in other Latin American countries that implemented standalone policies.[viii]

Yet optimizing diets is not just about reducing consumption of harmful foods and ingredients – it’s also about increasing nutrient density and intake of essential vitamins and minerals. Large-scale food fortification programs have been a global success story in reducing malnutrition. Today, more than 80 countries fortify staples such as flours and rice with vitamins and minerals, with significant health impact.[ix] Food fortification with multiple micronutrients has been associated with reductions in iron-deficiency anemia by 72 percent and in deficiencies in vitamins A by 58 percent, B6 by 91 percent, and B12 by 58 percent. In Costa Rica, for example, folic acid fortification led to a decrease of 51 percent in the prevalence of neural tube defects in 12 years.[x]

Now more than ever

These inspiring examples highlight the power of purposeful policy to improve diets and health for the whole population. By focusing on overall dietary patterns rather than individual nutrients or foods, approaching food policy systemically with mutually reinforcing actions, addressing both the “health-positive” and “health-negative” sides of the food equation, combining fiscal policy and regulation with food environment actions, strategically leveraging food procurement, adopting “food is medicine” approaches, and investing in nutrition research and innovation, governments and societies can make a huge difference in their citizens’ lives.

The bottom line: yes, smart policy can drive better diets and health for all – and that is more urgent now than ever.

This article first appeared in Nutrition Hub on September 9, 2020, and is reposted with permission.

References:

[i] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/0/face-fat-fault/

[ii] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-obesity-strategy-unveiled-as-country-urged-to-lose-weight-to-beat-coronavirus-Covid-19-and-protect-the-nhs

[iii] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/jul/03/boris-johnson-vows-to-review-whether-sugar-tax-improves-health

[iv] https://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/nutrition/documents/compilation_salt_en.pdf

[v] SAPEA, Science Advice for Policy by European Academies. (2020). A sustainable food system for the European Union. Berlin: SAPEA.

[vi] Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, et al. Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2006;354:601–3.

[vii] http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/259402/Successful-nutrition-policies-country-examples-Eng.pdf

[viii] Taillie LS, Reyes M, Colchero MA, Popkin B, Corvalan C (2020) An evaluation of Chile’s Law of Food Labeling and Advertising on sugar-sweetened beverage purchases from 2015 to 2017: A before-and-after study. PLoS Med 17(2): e1003015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003015.

[ix] Das_JK, Salam_RA, Mahmood_SB, Moin_A, Kumar_R, Mukhtar_K, Lassi_ZS, Bhutta_ZA. Food fortification with multiple micronutrients: impact on health outcomes in general population. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD011400.

[x] Barboza-Arguello MPB et al. Neural Tube Defects in Costa Rica, 1987–2012: Origins and Development of Birth Defect Surveillance and Folic Acid Fortification. Matern Child Health J. 2015 Mar; 19(3): 583–590.